Psychologist Carol Dweck (2016) has studied mindset in students. This is a powerful framework for helping students understand their habits of mind and their approaches to activities that feel difficult.

Reference: Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset : The new psychology of success. Random House.

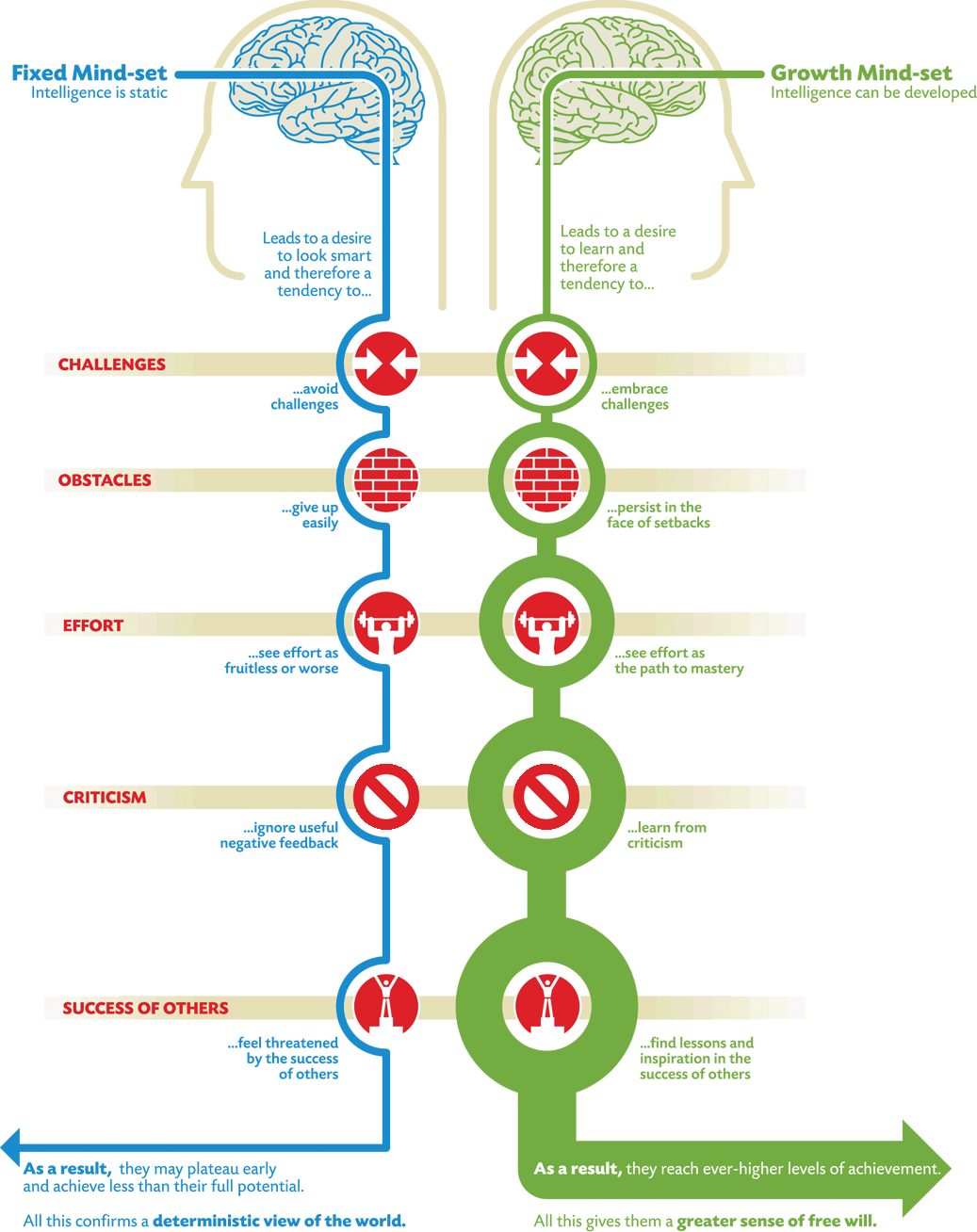

With a fixed mindset, students believe that their talents and intellect are fixed and their performance is predetermined (e.g., “Of course I failed that test – I’m not a math person”). When we operate with a fixed mindset, failure is confirmation of this personal weakness.

When we operate with a growth mindset, we see failure as a learning opportunity (e.g., “I missed that question on the knowledge check quiz, but I can examine what I did wrong and discover strategies to improve”). When students are encouraged to learn from failure or mistakes by reflecting on what went well and what they could adjust or change, they are guided toward a growth mindset.

A growth mindset can counteract stereotype threat (Canning et al., 2022; Lee et al., 2024), a common source of imposter syndrome, in which people may have absorbed implicit messages about how they are expected to perform based upon some aspect of their identity and corresponding social stereotypes.