Short Description:

Provide the foundation for any course. Instructors who connect course learning objectives, assignments, activities, and assessments provide students with a clear path to success in their course.

Details for Implementation

While the jargon of curriculum development (backward design, alignment, learning objectives, significant learning, etc.) can feel initially overwhelming, the underlying concepts make intuitive sense. For instance, backward design can be made familiar with a travel analogy: Just like when planning a trip, you want to clearly understand your destination and ensure that the route you are planning is smooth and travels through desired stops along the way. Implementing these evidence-based strategies places an emphasis on student learning and makes decision-making about teaching much easier.

Backward design for significant learning is a best practice for all modalities. Faculty engage in these intentional design processes prior to teaching, however, it is important to communicate design choices to students once the course begins.

The VTSU Online template includes weekly pages with the the requirement for faculty to define measurable learning outcomes for each week that align with the course-level learning outcomes. This structured, transparent communication for students is essential in an asynchronous learning environment, as you make clear to students your expectations for their learning (and what you’ll be assessing) within a given week.

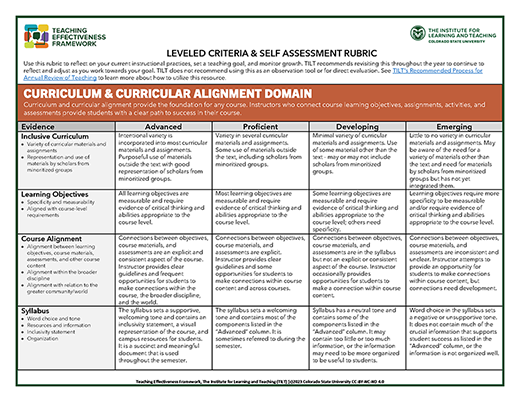

Use the self-reflection rubric as you consider your own teaching practice and use of instructional strategies. Download the file to get started.

Departmental curricular alignment, known as vertical alignment, is a key support for our learners. Ultimately, large scale alignment for a major, program, or course of study is done at the department level by collectively examining the terminus outcomes for graduates and identifying which courses support those competencies. Every department at the university participates in program assessment and vertical alignment is often a component of program review. Similarly, many disciplines have accountability to external accreditation bodies and there is a recent increased emphasis by these organizations in expecting departments to show alignment of learning objectives, assessments, and student success.

At a more granular level, instructors need to know how their course(s) fit into the larger scope of the major and how their course outcomes are aligned with the forward trajectory of the major. Every instructor brings personal perspective and expertise to their courses and it is not expected that all sections of a single course are identical. Nor should the alignment work eliminate academic freedom; rather, alignment is intended to identify the learning progression so that students who enter our courses are prepared by prior courses and that our courses prepare students for their next level courses.

Two other lenses in curriculum alignment include (a) looking at how students gain necessary competencies germane to employment and being an active citizen, and (b) identifying gaps and redundancies. Your department alignment should examine how cross-cutting skills such as writing, durable/soft skills, or technology use are developed across and between courses. For example, students need support in early courses to be able to write extensive analytical essays in upper-level courses or to complete complex projects as seniors. Another outcome of reviewing and analyzing the progression of content competencies from one course to the next is finding gaps (who is actually teaching that?) and redundancies. With the continual press on instructors and students for enough time, you might find redundant topics that are already taught in another course or identify topics that are currently on your syllabus but are not critical to the course learning outcomes. Sometimes we inherit these artifact topics when we are asked to teach a course that was turned over to us by someone else. Sometimes we realize that a curriculum refresh is necessary due to changes in the field. Removing topics that have become outdated, are suitable for another course, or are not fundamental to what students need to learn might buy you more time to focus on what is critical.

Course Curriculum and Alignment

Course curriculum is the set of knowledge, skills, behaviors, and dispositions intended as outcomes for the course. As you plan your course, be mindful of how it falls in the sequence of courses for the major. Take time initially to compare your course learning objectives to the objectives for prerequisites and courses to follow yours. Don’t fall into the trap of believing you have to use a textbook as THE curriculum. Textbooks are written to satisfy broad audiences and are not intended to be the defining arbiter of what you should teach. Textbooks should be a resource FOR your curriculum.

Intentionally create content that deliberately reflects the diversity of contributors to your field. Consider the large issues in your field. What are the overarching essential questions? What are the meta considerations your students should be grappling with? For example, in a history course, how are the stories of individual people and groups represented? How might power and identity be used as fundamental lenses to specific historical events? With large themes and essential representations, you are then ready to begin course design and alignment.

Course design and alignment is known as backwards design. It has similarities to vertical alignment but is at the course level. To use backwards design, instructors (1) identify student learning objectives for the course (both at the end of the course and the progression through the course), (2) identify assessment evidence that will allow the instructor and student to gauge student mastery, and then (3) identify/develop course materials and class activities to support student learning. We start with the end in mind and work backward to the individual lesson design knowing that there is a logical connection from the beginning of the semester to the end but, it is all driven by the end-of-course outcomes. Alignment is based on careful planning and allows you, throughout the semester as you teach, to highlight the connections between readings, activities and assignments with the course learning objectives. This coherence sets students up for greater likelihood for success and can ensure that students can see the relevancy of their work. Align the rigor of your class activities, discussions, simulations, performances, and quizzes with the rigor of assessments; this will provide students insight as to how to prepare for upcoming assessments.

Learning Objectives

Learning objectives are measurable statements that convey what students should know or be able to do. A learning objective should include how students will demonstrate mastery. For example, “You will identify and describe factors that impact the long term viability of an ecosystem and you will convey those factors with a 1 minute, student-generated video.” As you develop learning objectives, consider cognitive complexity. A more complex learning objective for our example might be “You will summarize and analyze the factors (and their interactions) that impact the long-term viability of an ecosystem; you will submit a written 5-page report to inform the reader”. Consider the level of rigor of student work you expect and how you can scaffold increasing complexity throughout the course. You might first expect recall and application and later in the course expect higher level analyses and the creation of new artifacts. Of course, learning objectives also require you to consider student preparation. What assets do students bring to your course you can capitalize on? Where might there be gaps that can be filled by changing how you teach or by directing students to support services?

Levels of complexity and measurable verbs are available in Bloom’s Taxonomy. An alternate that some faculty use is Fink’s Taxonomy which offers a framework to write learning objectives based on level of learning. Each learning objective should map directly to a course level outcome. In addition to cognitive complexity, pacing of lessons, variety of lessons and alignment of assessments with objectives, keep in mind how you will engage and motivate students. Engage students with applications to real world situations and discipline specific scenarios. Provide frequent opportunities for students to make connections within the course, the broader discipline, and the world. Design activities where students make connections between content and student learning outcomes. Provide students with some measure of choice in demonstrating mastery.

Syllabus

Conveying the coherence of your course learning objectives, assessments, and lessons is done with a syllabus. The syllabus provides students with an opportunity to see how you envision learning happening while also forming a strong first impression. Keep in mind that students often do not know how to read a syllabus. Plan for this inevitability; help students understand your syllabus and refer to it often throughout the semester. Think about the language you use in your syllabus. First generation students and those whose first language is not English may be confused by jargon.

Consider your syllabus and what you want it to convey. What is the tone you want to set? A learner-centered syllabus helps set the stage for a shared learning environment and shifts the responsibility for teaching to student learning (Bart, 2015). A learner-centered syllabus is one that incorporates clear statements of goals and student outcomes and provides an opportunity to set expectations for students at the start of the course. When the syllabus is more learner centered, it can be used as a student reflection tool. An interactive syllabus can be a useful way to engage students and

Keep in mind that your syllabus needs to be accessible for all learners. With this in mind, the university has developed an accessible syllabus template that is updated on a semester-to-semester basis.