What Are the VTSU Modalities?

Vermont State University, through a collaborative process, has defined 10 course modalities.

- In-Person (INP)

- Face-to-Face Plus (F2F+)

- In-Person Hybrid (HYB)

- Hyflex (HYF)

- Online Asynchronous (ONL)

- Remote Synchronous (SYN)

- Remote Hybrid (RHY)

- Telepresence (TEL)

- In-Person and Fieldwork (IPF)

- Field Based (FDB)

All modality illustration were created by Samson Fickes, a graduate of the Illustration / Animation program at VTSU-Lyndon. This intensive BFA program gives motivated, talented visual artists the training in drawing and storytelling to develop a unique “visual voice,” which prepares them for a myriad of careers in the animation and illustration field. Small classes (capped at 18 students), expert faculty, and a curriculum that stays current with the latest industry standard best practices and software prepares VTSU alums to stand out in the creative job marketplace.

Modality Relationships

It can be helpful to conceptualize the modalities in relationship to one another, considering where interaction is facilitated – in-person, online, or a combination of the two, as shown in the image below.

- One modality (Field-Based) requires a personalized arrangement for interaction, dependent on the course.

- Two modalities (In-Person, and In-Person & Fieldwork) rely on fully in-person interactions.

- Three modalities (Online Asynchronous, Remote Synchronous, and Remote Hybrid) rely on fully online interactions.

- And four modalities (Telepresence, Face-to-Face Plus, In-Person Hybrid, and Hyflex) use a combination of in-person and online interactions.

Modality Selection Advice

It can feel daunting, with 10 modalities, to determine the best option for your course. Follow these five steps to intentionally and thoughtfully make your decision.

Step 1: Become familiar with the modalities and their similarities and differences

Each modality has distinctions that carry implications for how you and your students will engage with the course. Fluency with the various modalities will allow you to better select an effective way to design and facilitate your course. Read through the information in this advice guide, talk with colleagues, and consult with the Center for Teaching & Learning Innovation staff to talk through your questions.

Step 2: Explore multiple facets to define your goals for choosing a new modality

While increasing access to courses for remote students may be a common goal for adjusting to a new modality, there are other factors that you may be considering, such as access, flexibility, and equity. You will likely want to think about who your prospective students are (and their likely experiences with higher education). You will want to think about your capacity for learning and using technology for teaching. You will want to think about how your course fits within your broader program and whether a consistent modality throughout the program or diversifying modalities better serves your students’ needs.

Articulating these goals may require you to navigate competing priorities. For example, you may sense a need for flexibility if your students typically report that they are juggling school with a high volume of work hours (perhaps indicating value of asynchronous learning), but at the same time, you may recognize they also benefit from the structure provided by synchronous learning perhaps because they are still developing self-regulation skills. Which goal (flexibility or structure) is most important, and can you identify a modality (such as Remote Hybrid) that might allow you to meet both needs?

Step 3: Revisit the learning objectives for your course

The Learning Objectives for a course serve as a touchstone for making all pedagogical decisions. This may be a good time to refine your Learning Objective using the three criteria in Figure 2.

| Criteria | Guiding Question |

|---|---|

| Achievable | Will students be able to develop the necessary skills, knowledge, and/or values in the time allotted with the resources provided? |

| Appropriate | Is the learning situated for this particular group of students with a fitting level of challenge and complexity? |

| Measurable | Is a successful level of learning clearly articulated, can it be demonstrated by students, and can it be observed? |

Learning Objectives may express cognitive (knowledge-based), affective (values-based), and kinesthetic (skills-based) learning. When they are written in student-friendly language, they become a useful communication tool as well as an essential planning tool.

When the Learning Objective are achievable, appropriate, and measurable, reading them in the context of the modalities likely will raise ideas and questions. For instance, if a course has a skills-based element that you have previously scaffolded in-person (maybe you model it in-person, then have your students practice while you give in-the-moment coaching, then your students practice independently, then they demonstrate in front of you for formative feedback, then they demonstrate for a summative assessment), how might you translate that activity to other modalities? For instance, could this learning move to an online setting using videos to effectively capture your teaching and their learning? And if so, what kinds of technological considerations come into play?

You may find that you can see a pathway for using technology to achieve each of your Learning Objectives with relatively little change to the assessments and activities. You may fairly easily identify which modality or modalities could allow you to meet the goals you’ve set for the class (in Step 2) while still achieving the course Learning Objectives using your existing assessments and activities, just translated slightly.

However, you may also be struggling to translate your current assessments and learning activities to a modality with online components, and if so, then taking another approach will be helpful.

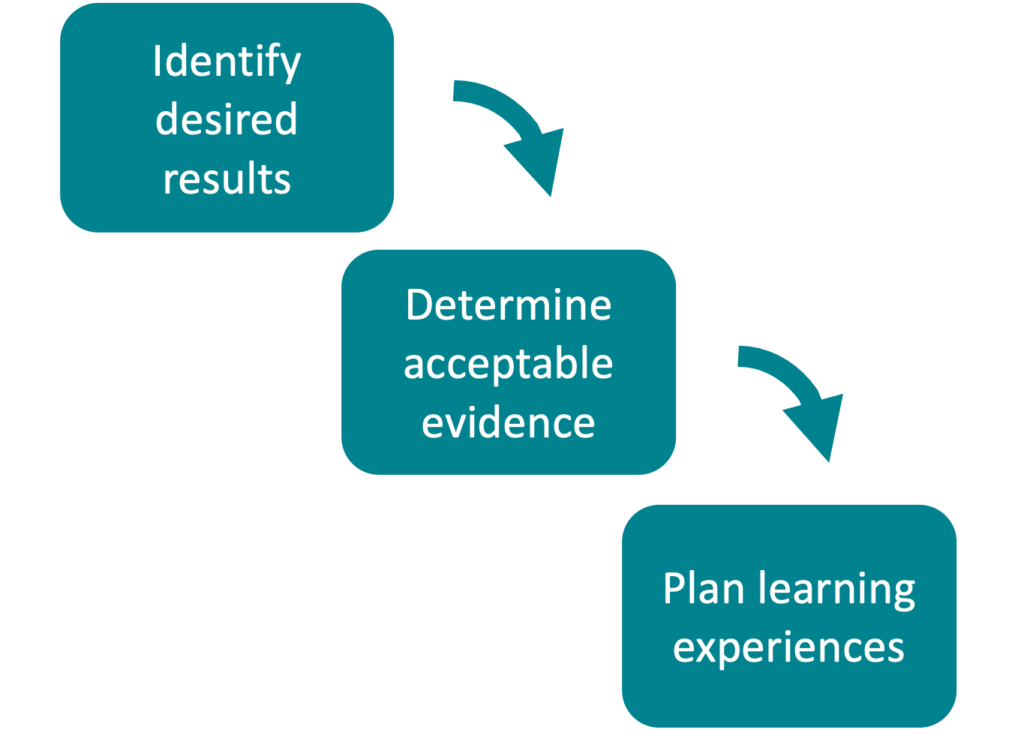

Step 4: Engage in Backward Design thinking

The work you did in Step 3 to refine your Learning Objectives is your starting point (identify desired results).

Now you get to engage in some creative thinking. There is often more than one way to assess (or determine acceptable evidence for) a single Learning Objective. As you consider shifting your course to a new modality, begin by brainstorming all the possible ways you could assess each Learning Objective. One concept to hold in mind as you brainstorm is that of “authentic assessment,” which focuses on students engaging in real-world application of higher-order thinking and skills. Authentic assessments may be contrasted with conventional assessments. Our colleagues at the Texas A&M Center for Teaching & Learning crafted an Alternative Assessment Guide for Hybrid/Online Teaching that will likely be helpful in getting your creative gears turning.

You may notice that your brainstorm of assessments includes both formative and summative options. This is ideal! Students will engage in deep learning when there are opportunities to evaluate their ongoing progress (with both self-reflection and expert feedback) toward a Learning Objective. This is considered formative assessment and is usually low- or no-stakes, giving you insight into needs for additional instruction and giving students a sense of their success progression. Additionally, you will need to identify the summative assessment activity where students will ultimately demonstrate their most comprehensive or advanced learning toward each Learning Objective (recognizing that sometimes assessments cover multiple Learning Objectives and sometimes there is a distinct assessment for each one).

As you engage in this brainstorming activity, you may see the possibilities for course modalities expanding – keep note of your ideas – what might work better in one modality versus another, what questions arise, etc.

In the Backward Design process, once you identify formative and summative assessments that align with the Learning Objectives, you strategically choose supporting content, homework, and class activities (plan learning experiences and instruction) to help students gain the appropriate knowledge, values, and/or skills. The facilitation of these instructional experiences may vary by modality. Again, it may be helpful to brainstorm ideas, imagining what you might do in one modality compared with another. These thought experiments will help you clarify your priorities, learning needs, and questions.

Step 5: Choose a modality

Following the steps to this point should have given you some new perspectives on ways to teach your course, likely identifying both possibilities and limitations. You may feel excited or you may feel daunted (or a combination of the two). All these feelings are valid. Designing and teaching a course in a new modality takes time, may feel experimental, and requires resources and support.

We all make decisions differently. You may have clarity about the modality you want to select for your course, right now, based on the thinking you’ve done. If so, great! But if you’re feeling confused, overwhelmed, or torn in multiple directions, it can be helpful to engage in a process for making this decision, likely one that you use in other facets of your life. Do you like making pro/con lists? If so, try doing that for each modality you’re considering. Do you want to talk through your thinking with a trusted colleague or CTLI staff member? Do you want to sketch out a week of your course in a couple different modalities to bring a greater sense of reality to what each would look and feel like?

As you move into the redesign phase, it is important to remember that you have many strengths as a teacher, and you can and should rely on these when contemplating your modality and course design choices. Additionally, while this document gives you a sketch of the design process and a few resources, you will almost certainly need and value additional support. The Center for Teaching & Learning Innovation is here for you; in the near future, we’ll be developing web-based resources. We will also continue hosting workshops and teaching retreats. And we are available for individual consultations. You are not alone!

Modality Matrix

| Modality Code | Modality Name | Requires Meeting Room Assignment | Requires Students to Attend Synchronous Meetings | Short Definition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| INP | In-Person | Yes | Yes | A course with in-person meetings at a set location and times, where the instructor and students meet in-person. |

| F2F+ (INP and SYN) | Face to Face Plus | Yes | Yes | A course where students can access synchronous class meetings in two ways: (1) attending class in-person at a set location or (2) attending class synchronously online over a video conferencing platform (INP and SYN). |

| HYB (INP and ONL) | In- Person Hybrid | Yes | Yes | This course includes both scheduled in-person course meetings at set location(s) and times and asynchronous online coursework. |

| HYF (INP, SYN, and ONL) | Hyflex | Yes | Maybe | A course that allows students to choose whether to attend classes in-person or online, synchronously or asynchronously (INP, SYN, and ONL). |

| ONL | Online Asynchronous | No | No | This course is offered fully online without in-person or synchronous class meetings. |

| SYN | Remote Synchronous | No | Yes | This course is offered remotely with pre-scheduled synchronous class meetings delivered through video conferencing. |

| RHY (SYN and ONL) | Remote Hybrid | No | Yes | This course is offered remotely in a manner which combines synchronous and asynchronous online participation (SYN and ONL). |

| TEL | Telepresence | Yes | Yes | This course is offered in a room outfitted with telepresence technology at a set location on specified days and times. Students attend the course in-person with the instructor on one campus while other students attend in a classroom outfitted with telepresence technology at another campus. |

| IPF (INP and FDB) | In-person and Fieldwork | Yes | Yes | A course that includes in-person meetings and a fieldwork component (INP and FDB). |

| FDB | Field-Based | No | No | Coursework is completed in a fieldwork location. |

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the difference between asynchronous and synchronous online courses?

Asynchronous online learning allows students to view instructional materials each week at any time they choose and does not include a live video lecture component. On the other hand, synchronous online learning means that students are required to log in and participate in class at a specific time each week. The main difference between asynchronous learning and synchronous learning is this live instruction component occurring at a set time. Learn more about asynchronous versus synchronous learning.

Should the Canvas LMS be used to support classes that are only offered online?

It is recommended that Canvas be used regardless of the modality that is selected. The platform is a vital resource for providing students with access to assignments, materials, and course grades.

Does the university have a standard contact hour requirement that applies to all modalities?

Yes – Students are expected to work at least two hours a week outside of class for each academic credit they receive in addition to one hour of instructional time.

Are all students eligible to take courses in a fully online format?

No – Veterans and international students may need to register for an in-person section of a Face-to-Face Plus or Hyflex course to comply with federal regulations pertaining to VA benefits and SEVIS.

What is the role of the Center for Teaching & Learning Innovation?

The CTLI supports the innovative pedagogical advancement of faculty for the purpose of fostering the professional and personal growth of each student.