October 2023 | Issue 3 | Volume 1 | Previous Issues

Small Interventions for Academic Success

We imagine that you (and your students) are grateful for this fall break week – a chance for everyone to recharge, catch up, and take a breath. At the same time, the “honeymoon period” of the semester is waning, and students (and you, too, perhaps) are likely feeling the immensity of the work still yet to come.

As classes resume after break, it’s a good time to survey your students to understand what is energizing them and what is stressing them about your class. A simple three-question, anonymous survey can yield actionable information:

- What would you like to see us stop doing that isn’t being effective for your learning?

- What would you like to see us start doing to better support your learning?

- What’s working well for your learning that we should continue doing?

It can be helpful to summarize the feedback and share it (in aggregate) with your students, along with your plan for response and changes. Students will find it valuable to see the trends in feedback and the outliers. And they’ll respect you for taking their feedback seriously and explaining your pedagogical choices.

In addition to responding to the good ideas that emerge from student suggestions, connecting individual students with university resources (e.g., tutoring, student success advisors, multilingual student services, wellness services) can help lighten your burden and support your students holistically.

In this month’s newsletter, we’re highlighting resources and strategies that can enhance your students’ learning, both in the classroom and more broadly within the institution.

As always, we in the CTLI are here as a resource for your teaching. Is a teaching task taking more of your time than you wish it would? Are you looking for fresh ways to get students engaged with your course content? Have you been thinking about changing an assessment for a while but need some help actualizing your vision? These are the types of issues that we’ve consulted with your colleagues about and are ready to work with you on as well.

Faculty Spotlight

In this third issue of the Vermont State Educator, we are highlighting the background, experiences, and perspectives of mathematics professor, Linda Segovia Wise. As an educator and first generation student with previous experience working in the TRIO program as well as her faculty role in the university’s F2F+ modality pilot, we are pleased to share her thoughts and perspectives on supporting the students of Vermont State University.

Please tell us a little bit about your background and what brought you to VTSU.

I started working at VTSU as a part-time tutor for math and physics in Williston while I worked on getting my teaching license in 7-12 Mathematics. Under the mentorship of VTC’s Academic Skills Coordinator, Dan Boyce, I applied for a full time position in the TRIO program in Randolph. Although I was hired as the Math/Science Skills Specialist, my position grew as I took on more of the tutor coordination and I was reclassified as the STEM Specialist/ Tutor Coordinator. A few highlights from my 7 years of service in the TRIO community include- Assistant Director of VTC’s Summer Bridge program, and President-Elect of VEOP (Vermont Educational Opportunity Programs). My work in TRIO inspired me personally as a Latina Mathematician and as a first generation college student to fight for access to education for all. I was fortunate to be able to adjunct for the math department while I was in that position and it nurtured my goal of teaching mathematics. When a full-time Mathematics professor position opened, it felt like a natural move. I am very grateful to have inspiring, nurturing, and supportive colleagues in both the TRIO and Mathematics community.

What are your favorite things about teaching at VTSU?

I’ve always been interested in mathematical modeling so getting to work with students who are directly applying the math they learn to their field is really rewarding to me. I especially enjoy working with non-traditional students and students who do not like math. Their resilience inspires me.

How do you encourage students to work with our academic support department when outside tutoring could be beneficial?

Two main barriers for students that I’ve identified are the scary unknown and the stigma associated with asking for help. I pull back the curtain on tutoring by inviting a representative from the Academic Support department to my classroom to introduce themselves and share what students can expect in a tutoring session. Building relationships with each students has been the most powerful tool in normalizing failure and asking for help. I focus efforts in building relationships early on so they are comfortable communicating with me and more open to referrals for tutoring. My favorite activity to get to know students is an Introductions Discussion Board in which students share their thoughts about a mathematician that they are able to relate to. In the fall they choose from Latinx & Hispanic Mathematician profiles, in the Spring from Black Mathematician profiles, and in the summer from Indigenous Mathematician profiles. The intimate stories students share about themselves and the struggles they’ve overcome never fails to give me goose bumps.

As an experienced F2F+ instructor, what technology and strategies have been successful in keeping your students engaged?

I post electronic notes before class (with OneNote) and have students read through it as pre-class work and submit a couple of questions they have. I think of this pre-class work as priming their brains for our learning time together. When they come to class, I use their questions to focus the lesson and activities on where the needs lie. During class I use Nearpod, Zoom polls, and group work to keep “Roomies” (in-person students) and “Zoomies” (remote students) engaged. I’ve found that students are not engaged during class because they are either bored or lost. I use the Zoom polls to check-in with students and keep track of their attention. Seeing students work in real-time in Nearpod keeps them accountable and helps guide my teaching. Of course, with any dependence on technology it is challenging when it doesn’t work. With face-to-face students I can scrap the technology when it doesn’t work but with remote students, I need to have a back-up plan. I record all of my classes if they have trouble with Zoom and share my screen in Zoom in case students have trouble engaging in Canvas or Nearpod during class. I’ve also learned to introduce new technology slowly, to accept that there will be issues that arise, and allow for space for working out those issues with low stakes activities.

Do you have any recommendations for faculty members who are interested in teaching in the F2F+ format?

Do a practice run with someone that has taught in the F2F+ format before the semester starts! It’s more juggling than you expect with managing the Zoomies and Roomies, and figuring out what tech works best for your teaching style. A couple of things I do now to make space for that juggling is post all in-class materials and links to Canvas before class including an independent assignment students start on their own at the beginning of class. Teaching F2F+ has forced me to be more intentional in my teaching practice.

Summary of Literature: Teach Students How to Learn

Now, more than ever, students need help to learn how to “do college.” Sometimes called the hidden curriculum of college, academic skill development—time management, studying skills, reading strategies, and communication approaches—is essential for success. Some students come to college with these skills, but most gain them through trial and error, emulating peers, or (in the most fortuitous circumstances) with the coaching of an advisor or mentor.

Acquisition of these academic skills has a positive effect on retention. If all students are taught to become more adept with these skills as early as possible, we should see more equitable outcomes. Additionally, supporting students to develop academic skills in the classroom is a proactive intervention. When all students are more equipped to “do college,” panicked emails about missed deadlines or requests for extra credit at the end of the semester are reduced.

An argument can be made that attention to academic skills belongs in the curriculum. A college degree signals skill development beyond disciplinary aptitude. Earning a diploma indicates that graduates have demonstrated effective time and project management, can independently learn new and often complex information, can manage stressful circumstances, know how to communicate with a range of constituents, and can use information literacy skills for inquiry-based research. If we expect these skills to be an outcome of a college education, then teaching these skills becomes integral.

Dr. Saundra McGuire wrote the book Teach Students How to Learn: Strategies You Can Incorporate in Any Course to Improve Student Metacognition, Study Skills, and Motivation in 2015 and it is as relevant today as it was then. This text is easy-to-read and is loaded with practical tips for helping your students learn better. The strategies shared have wide application across the curriculum. For example, being explicit with students about Bloom’s taxonomy and how your course objectives align with it may help students compare prior learning experiences where they might have been at, say, an “Understand” level to a college experience where they might be expected to demonstrate an “Analyze” level. Several of the ideas for reading and studying are especially useful for classes that rely on higher-stakes exams and traditional textbooks.

If you’re interested in learning more about incorporating metacognitive strategies in your classroom, come to an upcoming workshop (more information and registration links are at the bottom of this newsletter).

Teaching Tip: The Myth of Learning Styles

A pervasive myth in education is that each individual has a single “learning style.” You may have even been asked to take an assessment, at some point in your educational journey, to identify your particular learning style (e.g., visual, kinesthetic, auditory). Unfortunately, the research does not substantiate this hypothesis. Rather, learners all learn across learning styles, and may have contextual preferences for various approaches to learning, but this flexibility is in fact a huge advantage to believing one a singular approach will work.

It has been found that matching instructional strategies to a particular learning style, such as using visuals to teach a “visual learner,” does not improve learning for that particular student (Pashler, McDaniel, Roher, & Bjork, 2009). Worse, using the wrong sensory modality for instruction for some content may impair learning if the content is better suited to learning strategies delivered in another modality. For example, providing a lecture on knitting to an “auditory or verbal learner” will not improve learning if this is the only form of instruction. All learners will benefit from visual instruction and will require hands-on practice (kinetic learning strategies) to learn to knit.

Why the language we use matters when we talk to students about learning strategies and preferences.

The myth of “learning styles” persists for several reasons. One source for this misconception is the genuine need to accommodate individuals who cannot access materials in a particular modality. A second source is based on personal experiences with preferred activities. Some people prefer to read a book whereas others prefer to watch a film. If we talk about “learning styles” when we mean to talk about preferences, we inadvertently reinforce the false belief in “learning styles.” Language matters.

Certainly, some individuals have physical or cognitive characteristics that impair accessibility to learning in that modality. Hearing impairments create obstacles for lecture-based instruction. Dyslexia and other reading disabilities limit the accessibility of written materials. Visual impairments (blindness, or, in some cases, color blindness) interfere with learning from images. Limitations on mobility or fine motor skills make hands-on learning activities less effective. The fact that a particular modality is not accessible to a student does not mean that the student has a “learning style.” Materials presented through one sensory modality are simply not accessible to them for learning.

Similarly, preferred activities are not “learning styles.” We may enjoy some activities more than others, but our preferences do not mean we cannot learn if we use a less preferred activity. We might be more motivated to engage in a learning strategy that uses our preferred learning activity. If I like to watch videos more than I like to read, I might be more likely to complete an assignment that requires watching a video than one that requires reading a text. However, my preferences do not mean I will learn more by watching the video than by doing something else (e.g., reading or hands-on practice).

Different content and skills are sometimes learned best when students use specific modalities to interact with the content, regardless of the learner’s preferred activities (Bruff, 2019). For example, botony students will learn to identify plants more accurately if they study pictures than if they listen to a lecture or read verbal descriptions. Students in a poetry class will learn more about writing poems if they listen to poems read aloud than if they study images that depict the meanings of poems. Students of piano or dance must engage in physical activity to learn to play piano or dance. Interestingly, for all disciplines, students learn even better if they engage with the content and skills using a variety of modalities and learning activities (e.g., viewing images of art and reading verbal descriptions and analysis of the work).

Research on how people learn indicates that people learn best when they use multiple modalities to think about, practice, and encode new content and skills (Ambrose, et al., 2010; Bruff, 2019). If I read content, listen to a lecture, and study images and graphs related to the content, I am more likely to remember than if I think about the content in only one way. Research on memory and cognition refers to this phenomenon as the benefit of dual coding (Paivio, 2007) or breadth of processing (Anderson & Reder, 1979). If memory for new information uses both images and words, I have two ways to remember the information. If I forget the information coded in one modality, I might still be able to remember it by using the other encoding modality. Redundant systems work more reliably than a system that operates correctly with one procedure only.

Application: Effective Learning Strategies

- Present material in a variety of modalities: visual (pictures and graphics) and verbal (written and spoken).

- Provide concrete examples as well as abstract explanations of concepts. Discuss the connection between characteristics of the concrete examples and key elements of the abstract representation.

- Distribute learning activities over time. Repeated exposure and practice of new material spaced across intervals of time (a few weeks) produces longer-term learning. The passage of time between each exposure creates a different learning context. Variations in learning contexts create multiple cues that students can use to help them remember.

- Interleave review of examples of solved problems with activities that require students to solve problems independently. As expertise and problem-solving skill increase, ask students to spend less time studying examples of solved problems and more time working independently to solve new problems.

- Use quizzes and exams as opportunities to learn. Tests require students to practice retrieving information from memory. Students get feedback about retrieval success during the test and from their test scores. They can learn about how well the strategies they used to learn new material worked. Ask students to reflect on how they prepared for an exam and ask them to consider whether using a different study strategy might improve future test performance. Post-exam reflections (exam wrappers) help students calibrate their judgments about how well they prepared and how much they learned. These insights can guide their choices for future study activities.

Resources

Ambrose, S. A., Bridges, M. W., DiPietro, M., Lovett, M. C., & Norman, M. K. (2010). How learning works: Seven research-based principles for smart teaching. Jossey-Bass.

Anderson, J. R., & Reder, L. M. (1979). An elaborative processing explanation of depth of processing. In L. S. Cermak and F. I. M. Craik (Eds.), Levels of processing in human memory (pp. 385-404). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Bruff, D. (2019). Intentional tech: Principles to guide the use of educational technology in college teaching.West Virginia University Press.

Paivio, A. (2007). Mind and its evolution: A dual coding theoretical approach. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Pashler, H., McDaniel, M., Rohrer, D., & Bjork, R. (2008). Learning styles: Concepts and evidence. Psychological science in the public interest, 9(3), 105-119.

Claudia J. Stanny, Ph.D. is the Director Emeritus at the Center for University Teaching, Learning and Assessment at University of West Florida, Pensacola, FL

This article is released under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0).

Alum Spotlight

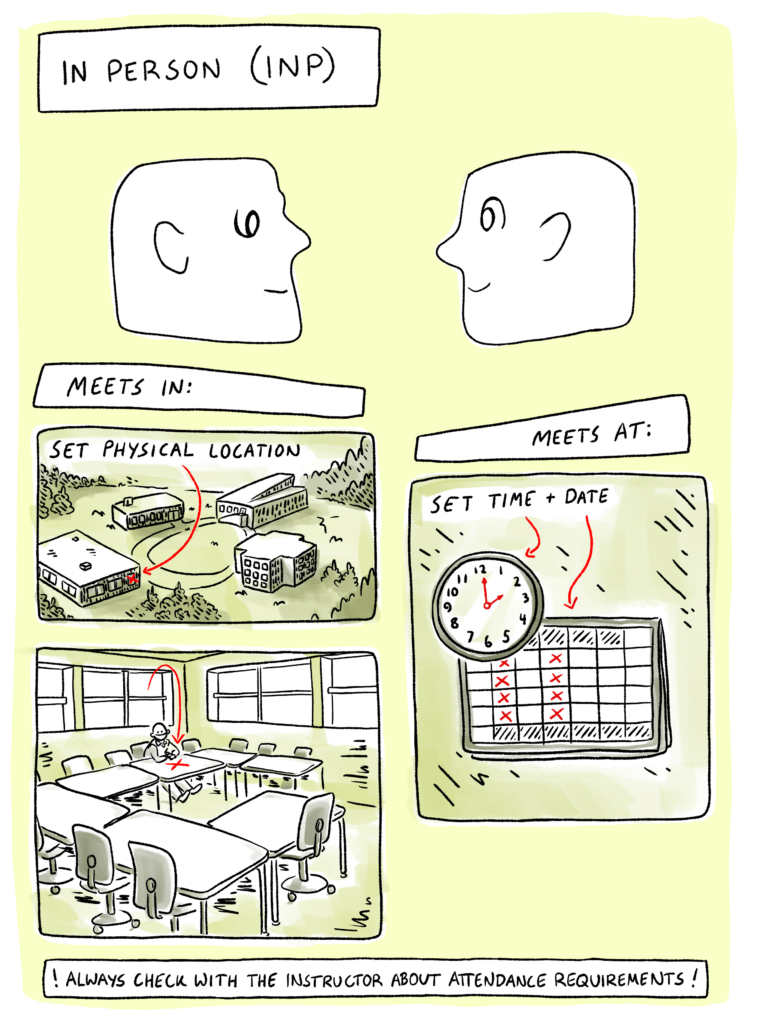

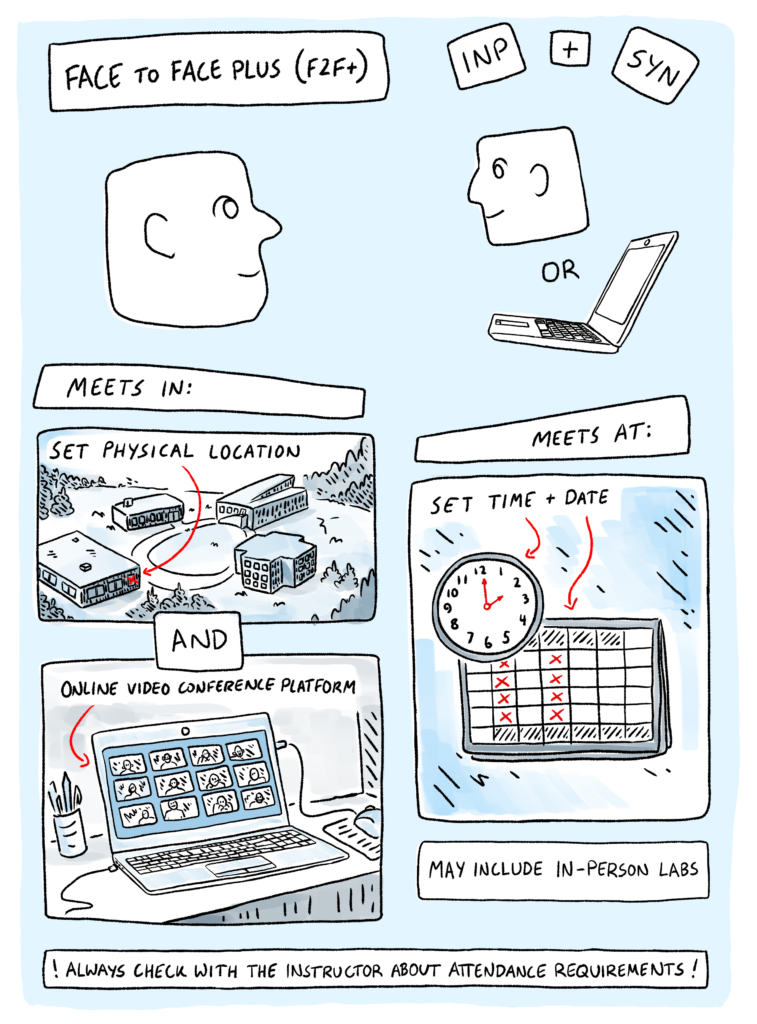

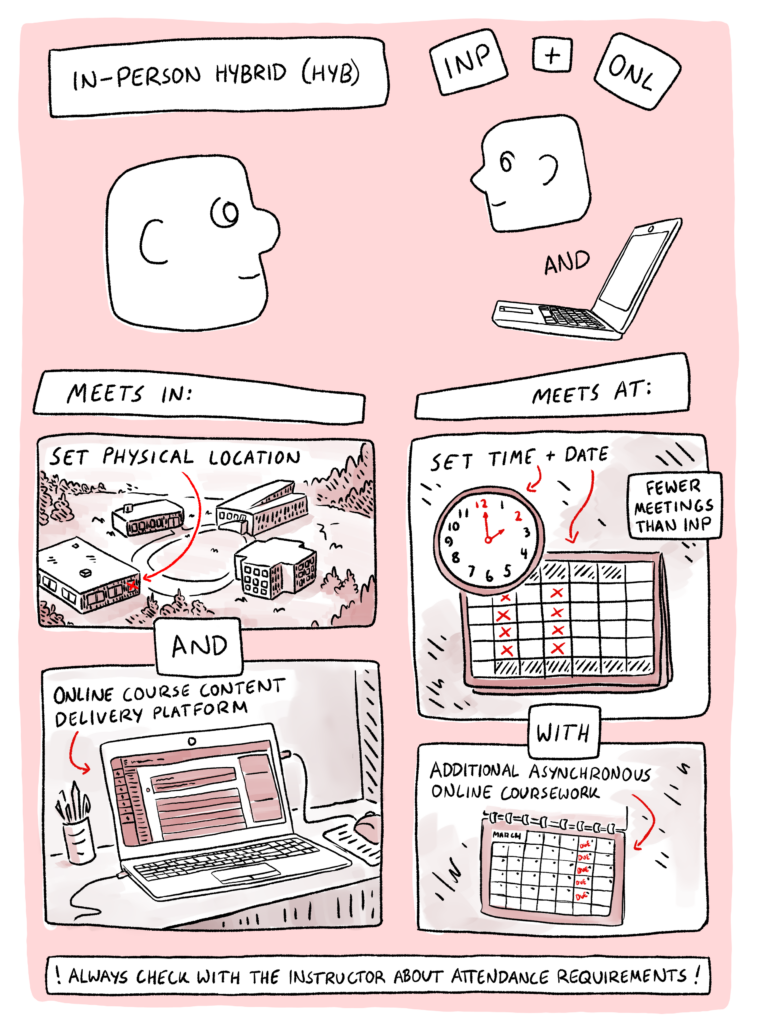

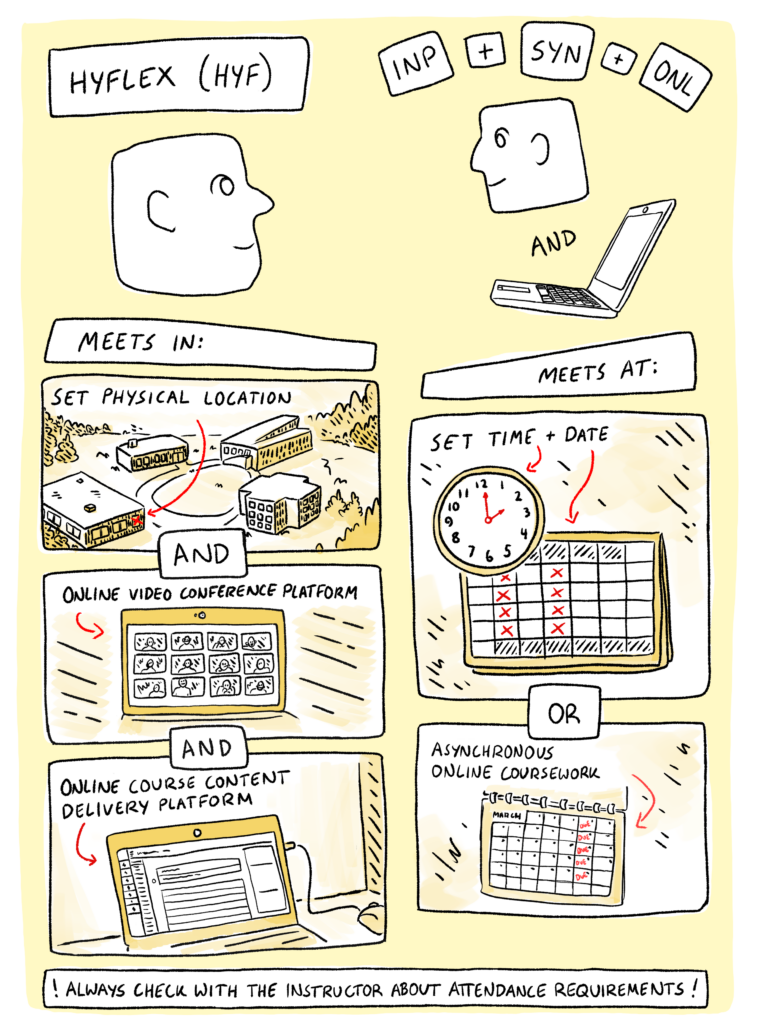

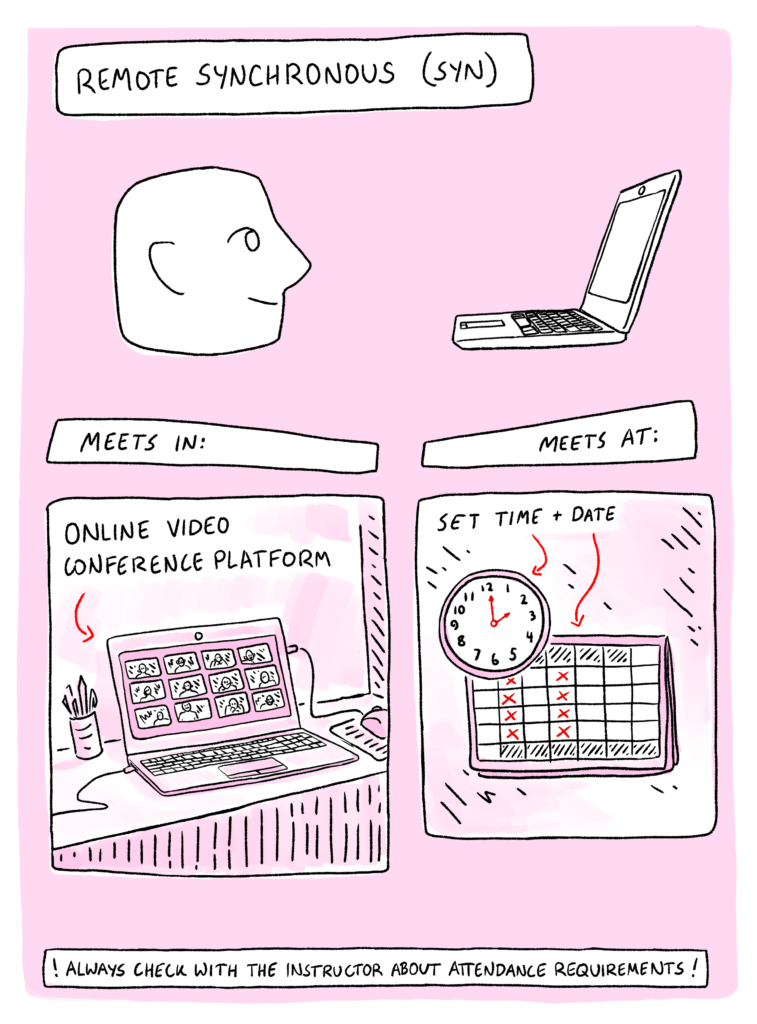

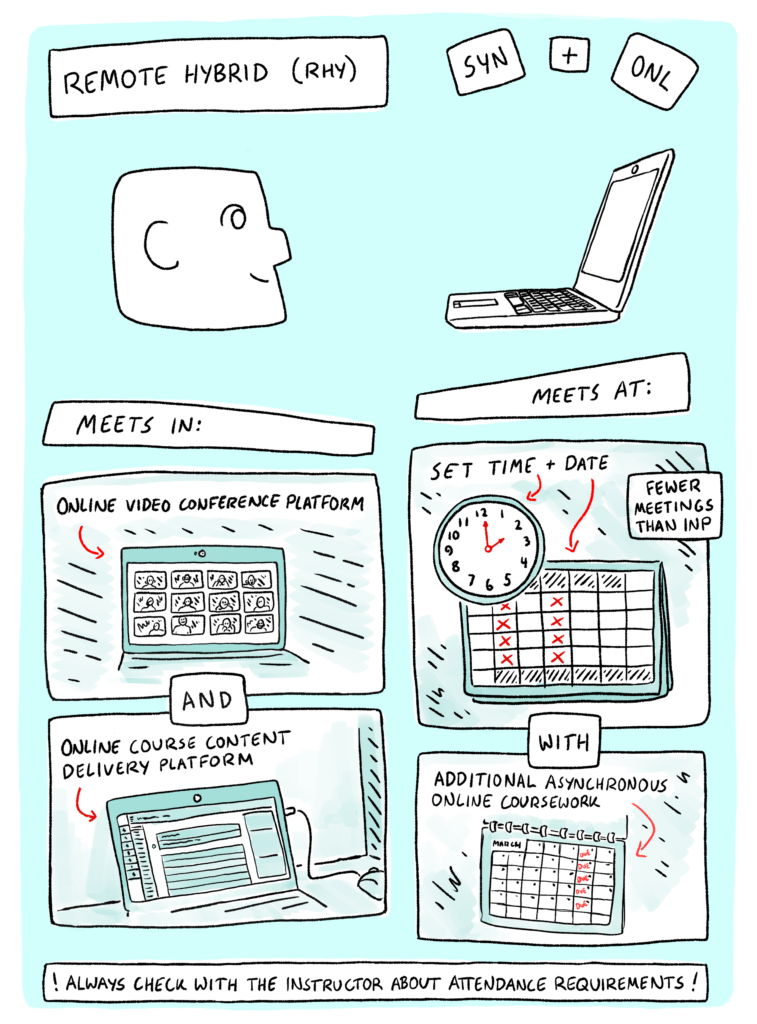

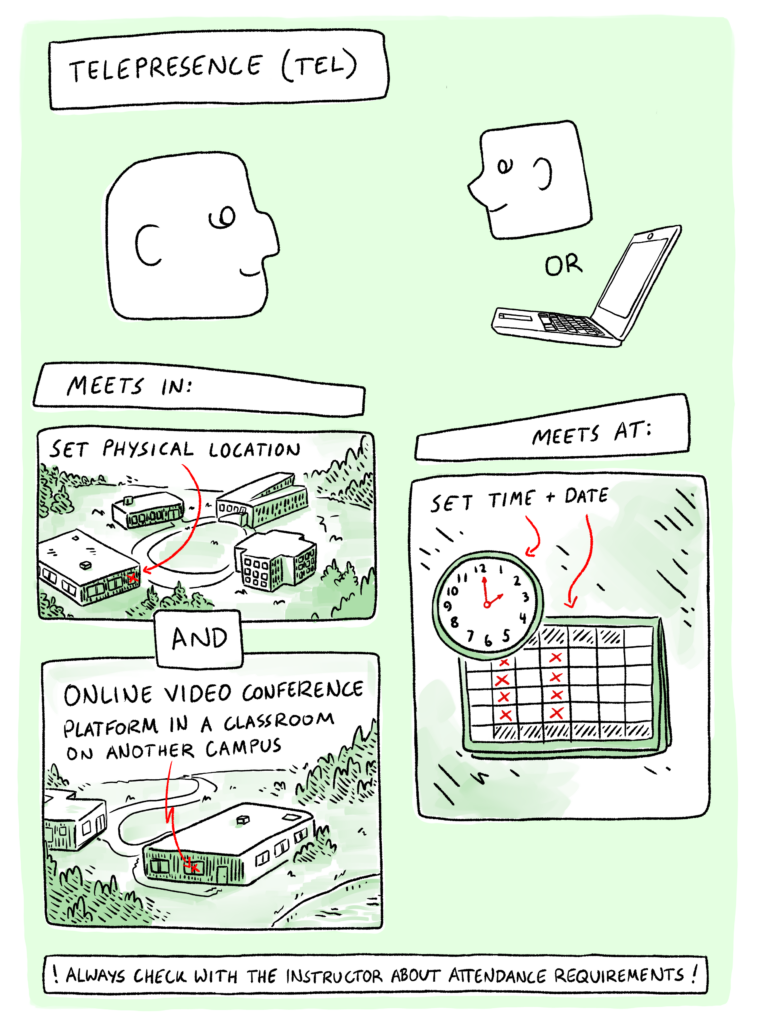

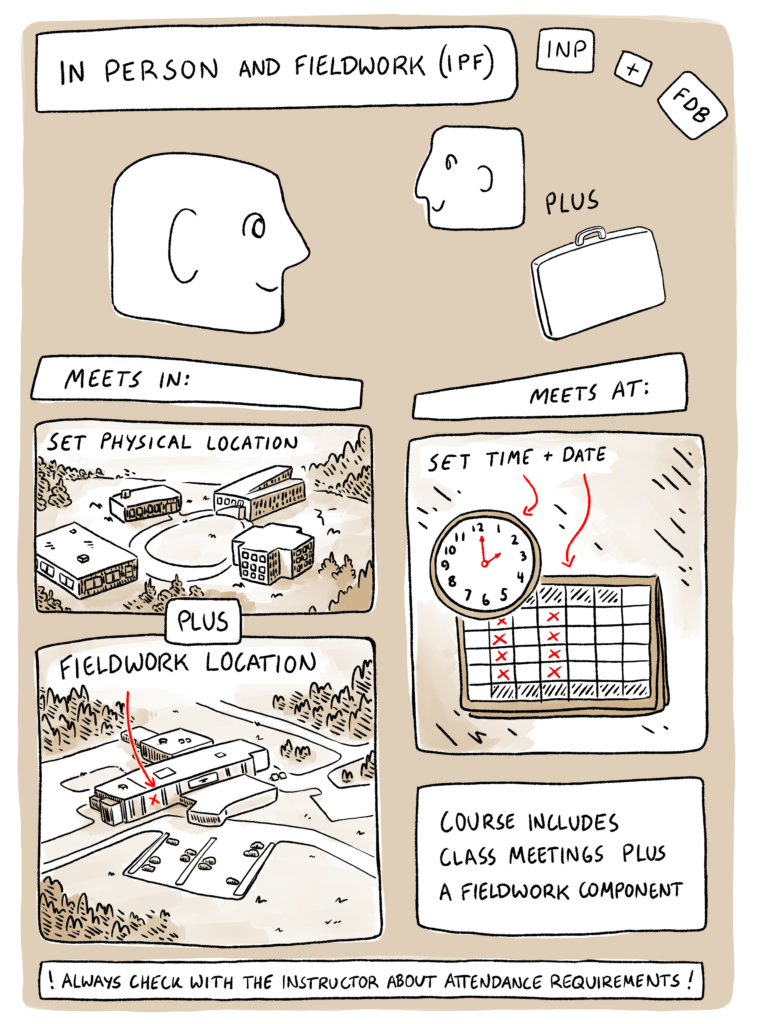

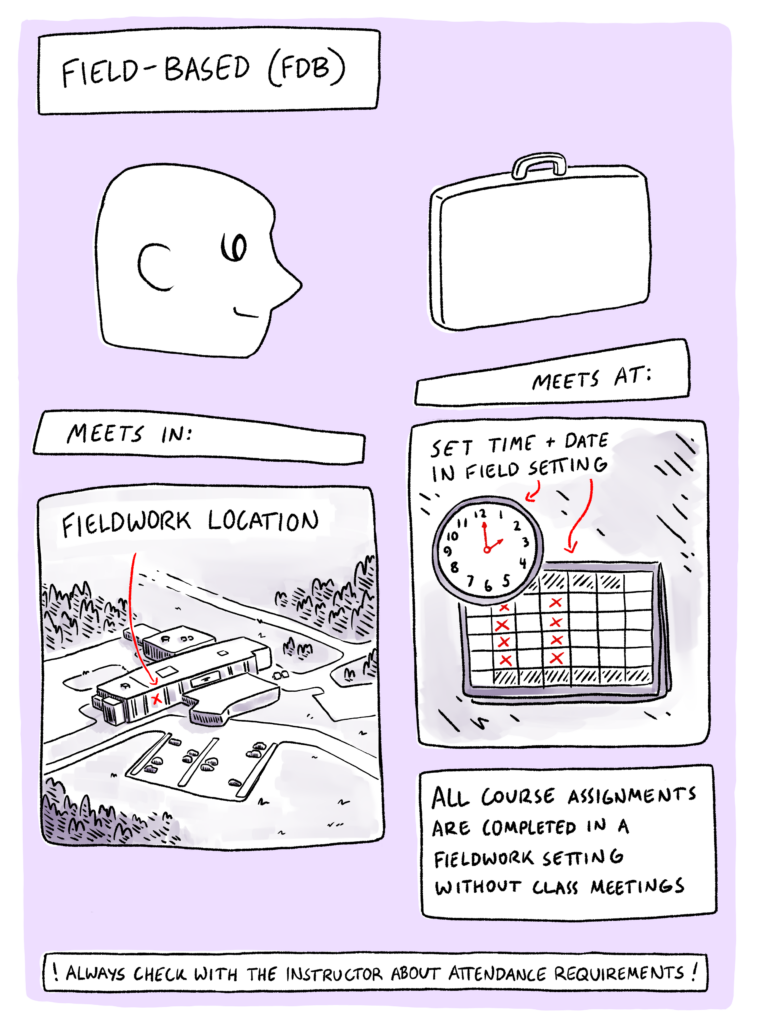

Below are graphical representations of Vermont State University’s ten course modalities that correspond to the descriptions provided in our Advice Guide for Designing a Course in a New Modality. Clicking on any image will open it full-size in a new browser tab.

These images were created by Samson Fickes, a graduate of the Animation & Illustration program at VTSU-Lyndon. This intensive BFA program gives motivated, talented visual artists the training in drawing and storytelling to develop a unique “visual voice,” which prepares them for a myriad of careers in the animation and illustration field.

Campus Partner – Multilingual Services

The establishment of Vermont State University Multilingual Services was guided by the principle that students who possess multilingual language abilities, including, but not limited to, international students, heritage language users, immigrant students, and refugee students, should be empowered and offered educational opportunities to effectively utilize their diverse linguistic and sociocultural abilities. This initiative aims to assist these individuals in navigating and capitalizing on the intricate fabric of their linguistic and sociocultural repertoires in higher education, so they will succeed and become competitive in the globalized contexts of study and working.

According to the Assistant Director of Multilingual Students Services, Mary Dinh, their services are accessible to both multilingual students seeking to gain a deeper understanding of their learning preferences and language use, as well as faculty members interested in optimizing the learning potential of their multilingual students.

Core Services

English Language Support and Customized English Language Resources: Multilingual Student Services (MSS) provides a diverse selection of English as a Second Language (ESL) courses, specifically targeting the areas of Developmental English (ESL 1020) and Academic English (ESL 1030). These courses are designed to cater to the needs of multilingual students who aim to enhance their proficiency in the English language, extending their usage beyond the scope of their major-related coursework. The Services is also engaged in collaborative efforts with several departments to tailor the English language curriculum, and asynchronous learning materials, to cater to the specific requirements of their student populations, with a particular focus on English for academic reasons (e.g., potentially, English for Nursing, English for Business Management, English for Sports…).

One-on-one English language tutoring and academic support: The Services offers individualized English tutoring sessions to facilitate the language acquisition process and enhance English competence. Students have the opportunity to meet with a tutor on a weekly or bi-weekly basis. The tutor will develop a customized curriculum and study plan for students to enhance their targeted English language abilities or assist students in successfully complete their capstone projects. Additionally, the tutor will provide guidance and recommendations for students to effectively review and prepare for significant assessments, drawing upon insights from the field of bilingualism sciences. The tutor will also provide recommendations for technical and electronic resources that students may utilize in conjunction with their in-person meetings., including tutor.com, MSS’s shared learning resources via OneDrive, and editing tools (Grammarly, thesaurus, bilingual dictionary, collocational dictionary, Google Translate, etc.).

Evaluation and learning observations of bilingual students to seek consultation with faculty members: Recognizing that many international students face unique challenges, Multilingual Services collaborates with academic departments to provide additional support for language acquisition and academic success. This evaluation aims to provide a thorough assessment that can assist instructors and students in maximizing the effectiveness of instructional and assessment methods for enhancing student learning outcomes. The Services have the capability to accurately identify the learning difficulties faced by students in their non-dominant language, whether they stem from linguistic difficulties (i.e., negative interferences between languages, lack of vocabulary), affective factors (i.e, anxiety with timed tasks), or cognitive overloads (i.e., could not suppress the interference of another language, unwanted code-mixing, repetitive sentence processing). Then, the Services will provide reports and engage in communication with the faculty and Department in order to offer recommendations and make proposals aimed at supporting students’ learning trajectories until they are able to fully utilize their multilingual talents.

Anticipated Needs

Based on the fiscal year 2022 data provided by the Vermont Agency of Education, there is a total of 1,801 K-12 students identified as English as a Second Language (ESL) or English Language Learners (ELL). It is anticipated that a significant proportion of these students would progress to higher education institutions. The population of multilingual students is expected to see growth within the realm of higher education due to the expanding access of university education to out-of-state and foreign students.

Multilingual Services Staff

Mary Dinh, Ph.D.

Assistant Director of Multilingual Students Services

mary.dinh@vermontstate.edu

A Bilingual Mind

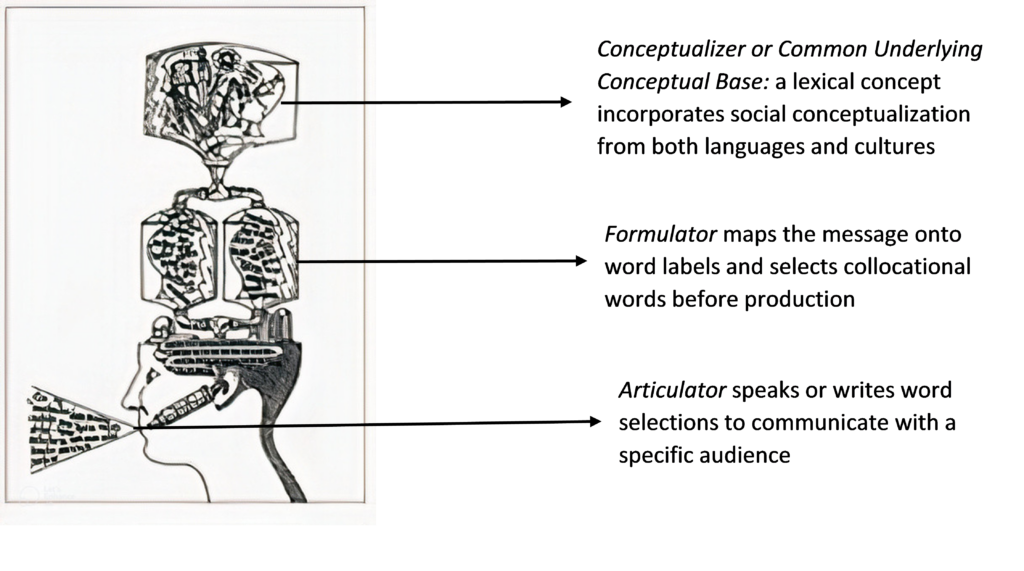

As a contributor to her field of study, Mary developed the figure below, as part of her dissertation.

“The bilingual is NOT the sum of two complete or incomplete monolinguals; rather, he or she has a unique and specific linguistic configuration.” – François Grosjean

Resource Spotlight: Tutor.com

On September 19th, Tawana Collins, a Customer Success Manager with tutor.com, provided a demonstration of their software which is now available in all Canvas sections. Their services include free one-on-one tutoring that is available 24 hours per day and extends across 161 VTSU courses. In addition, instructors have a faculty dashboard at their disposal, which can be used to gain insights into system participation at the course level. Given their breadth of services and extent of availability, tutor.com is a robust resource that complements the efforts of our internal academic support teams.

In addition to the demonstration, a follow-up discussion with academic support staff members from each of our campuses occurred. As part of the conversation, their roles, access to tutors, and other strategies for supporting our students were shared. To view the recordings of the tutor.com presentation or post-demonstration discussion, please select from the tiles below to launch the applicable video.

Testimonial

“Love the CTLI workshops. Helpful for thinking about pedagogy and my approach to teaching. Thanks for all you’re doing!”